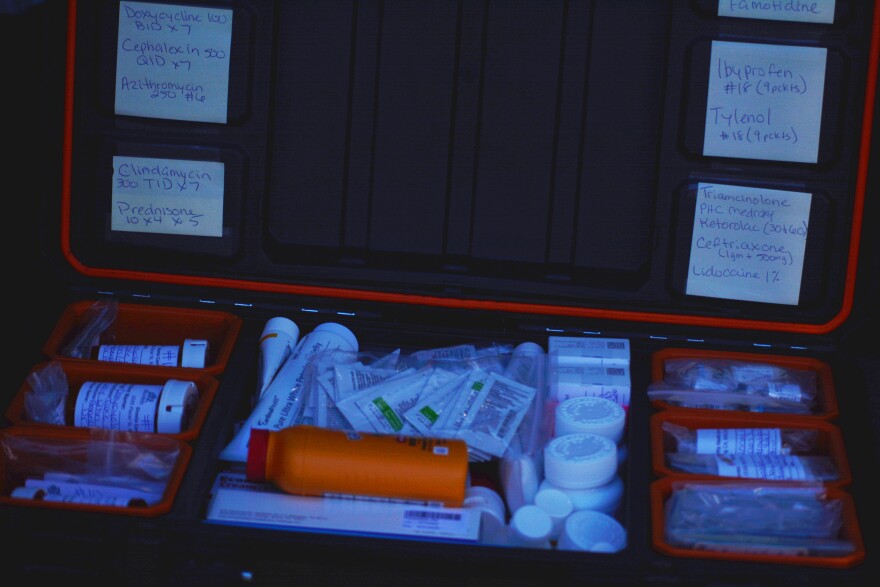

Dr. Kyle Patton is trekking through a field of dry and yellow grass on a recent Monday morning. His backpack is filled with medical equipment, everything from bandages to a stethoscope to anti-allergy and pain relief medications.

His medical assistant, Syan Joiner, walks with him. It’s windy and already getting close to 90 degrees. For the past 30 minutes, they’ve been trying to locate a camp belonging to two of their patients.

Eventually, Patton calls them.

“Hey, Jeremiah, you win the award for the most hidden camp,” Patton says then laughs on the phone. “We're normally good at finding folks, but you guys got us stumped.”

Patton is the medical director at the HOPE Program, which provides unsheltered people in Redding with continuous health care.

The program sends a doctor directly to residents who live outside on the streets or in encampments. It’s one of the few programs of its kind in Northern California.

“We've been doing this for a while now, so it's usually me trying to follow up with specific people that I know are needing help,” Patton says.

Finding his patients can be a difficult part of his day. Patton spends a good amount of time driving a van around trying to locate people.

“I ran into a patient on Thursday who was just in the hospital,” Patton says. “She said she's camping up there with her partner, so we're gonna try to see if we can track them down.”

After calling a second time Patton is able to find them. Their camp is set up in a secluded area off a trail to avoid being spotted, as the city has gotten stricter about camping.

First, their vitals are taken. Then, Patton begins conducting a full medical check up in the middle of the field.

Aside from the open land surrounding him, Patton works like any other primary care doctor. He reviewed both of his patients files before the appointment, and knows about their recent hospitalizations and conditions.

“It makes it difficult to keep appointments and stuff. Because I don't have a place where I can shower and clean myself and be ready for the day.”- Jeremiah Macierowski, unhoused Shasta County resident

Jeremiah Macierowski just got out of the hospital with a throat infection. He says being homeless makes it hard to get ongoing treatment when he needs it.

“It makes it difficult to keep appointments and stuff,” he says. “Because I don't have a place where I can shower and clean myself and be ready for the day.”

Patton checks on Macierowski’s throat, then asks if he’s been able to pick up his prescribed antibiotics.

Macierowski’s partner, Opalann Rasmussen, says Patton’s outreach is essential.

“By them coming out and doing this, it really does help a lot of homeless. I know that,” she says.

Rasmussen has psoriasis that is likely caused by living outside in Redding’s dry, hot environment. Patton discusses treatment for the rash, goes over birth control options, and also checks on how her recovery from a recent surgery is going.

It’s not uncommon for his patients to be dealing with multiple conditions at once, Patton says, noting health issues often compile when someone is homeless.

After finishing up with the couple, Patton heads off to look for his next patient.

Her name is Schlyane Standlee. Around five years ago, her right leg was crushed by the two wheels of a dually pickup truck.

The wound is still open and healing to this day.

Standlee has limited mobility in her foot, and it needs to be constantly monitored and rebandaged to prevent infection.

“It's not warm, it doesn’t feel fluffy like there’s an abscess underneath …” Patton says as he begins inspecting her injury.

Joiner, the medical assistant, tells Patton that the patient's temperature is good, and says Standlee doesn’t have a fever.

“This is starting to look more kind of uniform,” Patton says to Standlee. “The fact that it's kind of bleeding is a good sign.”

After Patton finishes the examination, Joiner wraps the leg back up.

Standlee struggled to get help for her wound before the HOPE Program. She says she only felt comfortable seeing Patton after another person in her camp received care from Patton first. The person then urged her to visit him, and she did.

“I used to run when I seen this van because I was embarrassed,” she says, laughing.

Now they check on her regularly to inspect her leg and redress it.

“Otherwise I wouldn't have been probably getting no care now,” Standlee says.

That kind of word of mouth is how Patton says he meets most of his patients. But he says the real challenge is staying connected to them so they can get follow-up care.

How encampment sweeps are complicating things

Like many places in California, Redding has been passing stricter laws about homeless encampments. It’s the result of a Supreme Court ruling last summer that allowed cities to enforce bans on unsheltered people sleeping outside, even if there is nowhere else for them to go.

Patton says the encampment sweeps are making his job increasingly more difficult — and hurting his patients.

A major reason is that removals lead to him seeing fewer patients in a day because they’re often moved around and he constantly has to find them again.

He points to his search in the morning for Macierowski and Rasmussen as an example.

“People who are unsheltered typically get this reputation of being hard to engage or treatment resistant. They don't want housing, they don't want health care. And that’s just not true.”- Brett Feldman, California Street Medicine Collaborative director

“These folks, like, we didn't know where their camp was,” he says. “We had to hike around on the other side, and then eventually we're able to find it. But that took time.”

Patton recently contributed to a guide with the California Street Medicine Collaborative about the health impacts of encampment sweeps.

It argues the state’s attempts to treat homelessness through enforcement are not working. And it explains how instead, these policies disrupt the relationships street doctors have been working to build.

The guide also gives advice to practitioners on how to mitigate the health risks caused by sweeps.

Brett Feldman, director of the collaborative, said he’s heard many misconceptions about visibly homeless people throughout his nearly 20 years in street medicine.

“People who are unsheltered typically get this reputation of being hard to engage or treatment resistant,” he said. “They don't want housing, they don't want health care. And that’s just not true.”

Street doctors are able to facilitate ongoing care by going directly to their patients. This builds trust, he said, which is essential for eventually getting someone housed.

Connecting people to services is what the HOPE Program is ultimately working to do. Health care is just the start of the relationship.

“When we provide care in their environment where they feel most comfortable, it's actually fairly easy,” Feldman said. “Usually we can begin to have a meaningful relationship with somebody on the first visit.”

The method is shown to be an effective way to help unsheltered people get off the streets, he said, highlighting that the collaborative has housed 30-35% of their patients every year since 2018.

But Feldman said removing people from encampments interrupts — and can even end — the doctor-patient relationship. This makes it harder to get someone housed if they struggle to take charge of their own treatment.

Kelly Koelsch is a drug and alcohol counselor for the HOPE program. She focuses on medication-assisted treatment and harm reduction, and also helps people transition into rehabilitation facilities.

“We had a date to go pick him up, we had the hotel voucher all set up. Then we got to the camp, and it had already been cleared out and he was gone.”- Kelly Koelsch, HOPE drug & alcohol counselor

Like Patton, Koelsch said encampment removals make her job harder and keep people from staying connected to resources.

It’s common for patients to lose their phones, medications and other essential belongings during an encampment sweep, she said. This can lead to the patient losing contact with their case manager until they end up in the hospital again.

Koelsch recalled an incident where the team had worked to move a person into temporary housing for around a year.

“We had a date to go pick him up, we had the hotel voucher all set up,” she said. “Then we got to the camp, and it had already been cleared out and he was gone.”

She hasn’t been able to find that patient again. She and Patton said a lot of time and resources were wasted.

In Redding, it usually takes about a year and a half to get someone housed, Patton said, and encampment sweeps complicate what’s already a lengthy and fragile process.

“If you think about all the steps that are needed, that's 18 months where you're trying to maintain continuity with the patient,” Patton said.

How the Grants Pass ruling changed things for cities

Last summer, a Supreme Court decision changed homeless policy across the nation. It made it so most cities don’t need to provide another option for shelter to be able to remove someone from public property.

Jurisdictions across California were quick to follow that ruling. Redding tightened its policies on encampment removals just two months after.

Last August, the city started giving half the notice time that it was going to remove a camp - going from 48 hours to 24 hours.

The new policy also added a “three strike” rule, where someone who has violated Redding’s outside camping laws three or more times can be removed without any notice at all.

In Chico, things work a little differently.

Due to a recent lawsuit and settlement — Warren v. Chico — the city must have a shelter bed available for every person it wants to remove, and offer it to the unhoused person before removing them. Seven days of notice is also required.

“There are very potent solutions to addressing homelessness in our communities. But it takes investment. It takes buy-in. It takes collaboration. We have to get on the same page and address the problem in a way that’s different than enforcement and displacement.”- Dr. Kyle Patton

The city of Chico tried to withdraw from that agreement recently, saying it was unworkable and expensive. But the judge denied their request.

Earlier this month, Gov. Gavin Newsom called on cities across the state to adopt his model for encampment removals. It encourages cities to clear camps as long as “every reasonable effort” is made to offer alternative shelter.

Patton said the main issue has to do with where resources are being directed.

“Communities are embracing encampment sweeps while not investing in the supportive services that our patients need to survive the sweep,” Patton said.

Homelessness is mostly a statistical issue in Patton’s eyes. He said it’s going to exist in California as long as there isn’t enough housing available for everyone.

“There are very potent solutions to addressing homelessness in our communities,” Patton said. “But it takes investment. It takes buy-in. It takes collaboration. We have to get on the same page and address the problem in a way that’s different than enforcement and displacement.”

NSPR reached out to the city of Redding for comment and did not hear back by deadline.